My dad's old sawmill

After my family moved to Canada, my folks went shopping for a permanent place to stay. Although the priority was finding a place with a house in good shape and enough land, what caught my dad's eye about the place we did end up buying was that it came with a sawmill. The place was a terrible mess, but the house in reasonable shape. The sawmill wasn't in perfect shape either.

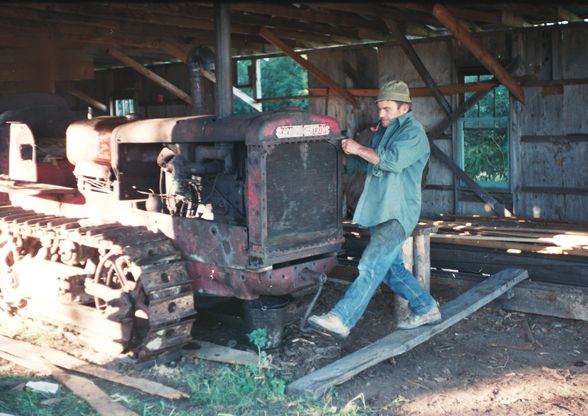

The sawmill had the fittings and such from an old steam powered sawmill that there was a fair number of during the first half of the century. However, power was provided by something a little more modern: A 1938 McCormic Deering bulldozer style tractor which had a power takeoff flatbelt pulley on the back.

The property also came with an even more modern payloader from the 1950's. Instead of a shovel, this payloader had a forklift fork on the front, and was used for moving logs and piles of wood.

Loading logs with the ancient payloader |

The payloader leaked oil when the system is pressurized. My dad never fully filled the hydraulics system on the belief that it might leak less when not fully full. Sometimes it ran out of hydraulic fluid with the cylinders extended.

Dropping the logs on the log deck

The loader's old flathead 6 cylinder gasoline engine was not terribly efficient, and also gave its share of troubles, and in recent years the generator (a predecessor of the alternator) no longer charged the battery, so we charged it with a battery charger between uses. Nevertheless, the thing was very useful and worked most of the time. Nothing like a payloader when you have to move stuff that weights a few tonnes..

Starting the 1938 McCormic Deering Diesel engine in gasoline mode

Even though the tractor prceeded the loader by about 20 years, its engine was more advanced. The tractor's engine was a 4 cylinder gas/diesel engine that was started by hand. The 'gas' mode of operation of the engine was strictly used for starting, as starting a cold diesel engine would not have been possible by hand.

By hand is actually a bit of a misnomer, because the engine could only be turned by inserting the crank at the right angle, and then stepping on it and giving it a kick. Each kick, if successful, turned the engine by half a turn. With a four stroke engine, the minimum number of strokes it should possibly take is three, and the record was getting it started in four kicks. Sometimes, on bad days, it took 40 kicks, which is 20 turns. Compared to a lot of cars, that's actually still quite good.

The tractor, in later years |

Once the engine was started (in gas mode), it was let run for a few minutes, After it was warn, a mechanism would release the switchover lever, and the engine would make a tremendously loud clacking and thundering noise as it switched. Starting on diesel, as far as I know, was done purely on momentum from 'gas mode'. For some reason, it never stalled on switchover.

Starting the tractor was sufficiently difficult that we always left it running during lunch. Starting it in gas mode while hot was next to impossible anyways.

The engine was remarkably fuel efficient. I later found an article about a certain tractor that that company built, and the engine was a great step forward in sophistication and fuel economy. It intorduced some modern technologies such as brass sleve bearings and overhead valves to engines of that size. It turns out that that engine was in that tractor.

Over the years, various things went wrong with the tractor. First the clutch, and custom parts had to be made. Then the injection pump started acting up periodically, and when the governor on it stopped working, my dad gave up fiddling with it. It was exposed to the elements for a few years, but has recently been hauled away buy a guy who is currently restoring it back to life.

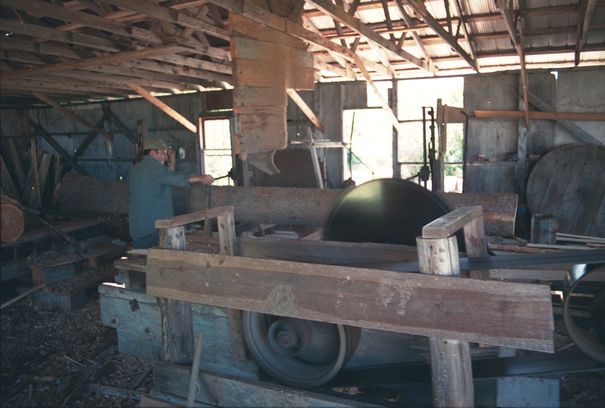

A log ready on the carriage ready for cutting

The carriage and tracks of this sawmill were much more solid than of the typical hobby sawmill of similar configuration. The carriage to hold the logs had solid cast iron parts, and axles of about 3" diameter steel. The main drive shaft on which the saw blade was mounted was also about 3" in diameter.

Main drive pulley

An ingenious system of flatbelts and friction wheels in the casing between the drive pulley and the saw blade allowed the control of movement of the carriage, which must have weighted way more than a tonne, with a wooden lever. This lever moved a tire back and forth, which would push against drums rotating in either direction. The tire was coupled with a U-joint to a drum which had about five turns of the steel cable coupled to the crriage. This mechanism worked remarkably well.

Cutting a slab before cutting boards

The first cut off any side of the log is called a 'slab'. This is essentially wasted as lumber. We cut those into firewood for heating the workshop.

This sawmill had no powered means of rotating the logs on the carriage. Instead, a canthook had to be used to flip the log by 90 or 180 degrees. I always found it remarkable how (relatively) easily a log is manipulated with a good cantook, although during normal operation, I was always the one on the other side of the mill piking up the cut lumber.

Boards are cut from a log by running it past the blade and back. The log is moved outwards by pushing and pulling the lever attached to the rachet on the carriage.

The blade would always get pulled into the log a bit on account of the angle at which it was mounted. However, it always pulled the same amount on each cut, so the net effect was not very noticeable on the boards cut.

The view out of the sawmill builing

My job, when we ran the sawmill, was to take the boards from where the above picture was taken, and sort them by thickness. My dad would always look at the quality of lumber as it came out, and decided how thick to cut it for what job as he went along. Operating the sawmill is a two man job minimum, and works better with three people working at it. My sisters always hated it when they had to help in the sawmill after my older brother went off to university.

The sawdust pile after several days cutting

Cutting logs with this sawmill produced a lot of sawdust. With the 1/4" kerf of the circular saw blade, 10% of the log was turned to sawdust at the very least.

The sawmill had a chain to pull the sawdust out from under the blade and out of the building. Beyond that though, when running it for a few days, the sawdust had to be spread out with a shovel to make room for more.

Once in a while, when the pile was big enough, a farmer would come and get it for his barn. This was always a relief to me, because it meant no shoveling for a whole day, and not shoveling as far the next day.

The saw blade being sharpened at mid day

The saw blade had these intersting replaceable teeth. This meant that the saw blade, unlike more primitive saw blade, always had the same diameter. Before replaceable teeth, the teeth as well as the gap between them always had to be filed down. There was one such saw blade kicking around, but we never used it, and it wasn't as big either.

Every few hours of operation, the saw blade had to be stopped, and my dad filed the teeth. This was especially bad if the logs were dirty. When milling towards dusk, you could see the sparks when he blade hit some of the dirt. This is why most sawmills peel the bark off logs before they mill them.

Once or twice, we ended up distorting the blade from overheating. To get it flat again, it needs to be hammered in a special way, and people who knew how to hammer such a blade were a dying breed. Once my dad got the hang of running the sawmill, I don't remember the blade ever needing hammering again.

During the heavy snow of the 1996-1997 winter (the year before the rest of Ontario got hit with the ice storm), most of the sawmill building collapsed. My dad knew that it might buckle under the snow, but he didn't really need the sawmill anymore, and didn't want to risk getting up on it to shovel it when it was so heavily loaded already. the sawmill is now exposed to the elements. The tractor and the loader have since been hauled away by a guy who is restoring them back to life. The actual workings of the sawmill have also been hauled away.

The whole sawmill was quite obsolete compared to some of the band saw mills that are available today, although a bandsaw mill is apparently less forgiving to unskilled operation.

Still, the sawmill was very useful. You just can't walk into home depot and buy 3" thick oak planks, and even if they had it, it would cost an arm and a leg. Getting logs was also difficult though, and most of the logs my dad milled were from his own property, cut down by my dad.

Related pages: